On Fairness

An axiomatic, and hopefully earnest, thought process to equality, fairness, and discrimination in the United States

The topic of equality and fairness has been on my mind for quite some time, partially because of the ongoing public conversation about it in the United States. As a casual observer, the soundbites I’ve been exposed to, for example on social media, or through mailing lists, have seemed rather partisan and unhelpful.

Prompted by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on June 29, 2023 about Harvard and University of North Carolina’s admission practices, and its immediate discussions, I’d like to contribute my own thought process, starting from first principles, to this conversation.

Axioms

Axioms are statements that are taken to be true. I hope the axioms I put forth below are uncontroversial.

Ax. 1: There is no universal definition of fairness

There doesn’t seem to be a universally accepted standard or definition of fairness. What one person considers fair might be grossly unfair to another person.

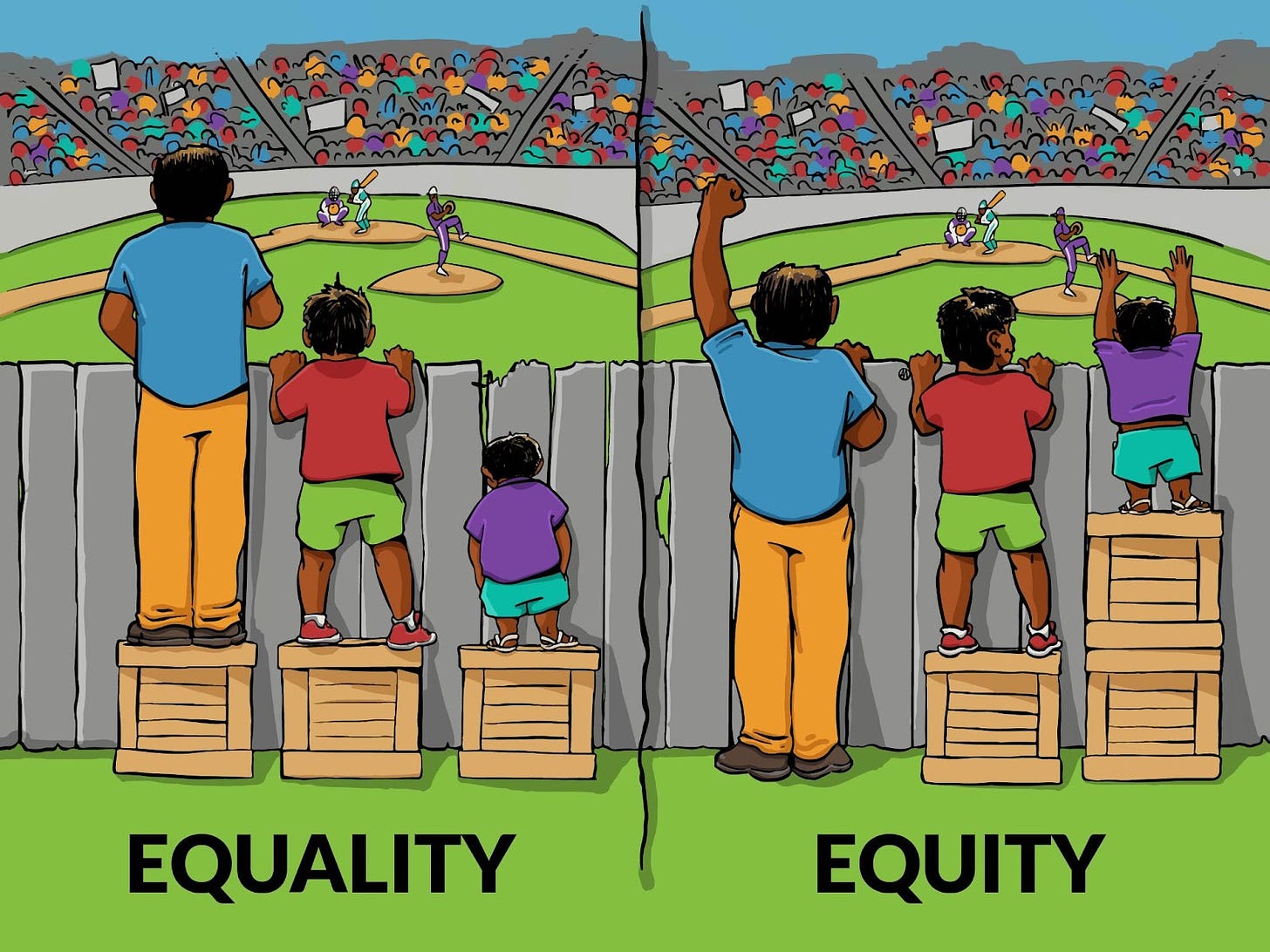

Below is a classic graphical illustration of “equality” v.s. “equity”1, that highlights this point in an extremely simplistic case. I contend that, while this hits a great point, it’s not sufficiently instructive for real world situations.

What if there are only 2 boxes instead of 3? What if the smallest kid still can’t see over the fence standing on 2 boxes? What if there are 10 kids and only 5 boxes?

I imagine different people could come up with different, albeit all “fair”, arrangements to the hypothetical situations above, which are closer to the real world.

Ax. 2: Resources are limited

Not everyone can get everything all the time. Perhaps this is tautological because what people want grows with what they have, so maybe it’s just a general truism that they’ll never be fully satisfied.

Even practically speaking, there simply isn’t enough “stuff” to go around. We don’t have the landmass to give everyone in the Bay Area an acre of land. We don’t have enough doctors to see everyone at a moment's notice whenever they need it, even with costs aside. And of course, there’s only 1 Ed Sheeran, so if you want to listen to him live, you have to squeeze into the limited space in his vicinity.

Ax. 3: There are inherent differences in people

Not everyone is exactly the same.

Some differences are biological. Some people are taller, some are lighter-skinned, some are born with a uterus, and others aren’t.

Some differences are social and cultural. With different backgrounds, families, and experiences, people speak different languages, develop different skill sets and interests, and have different preferences and opinions.

Not everyone actually wants to own an acre of land in the Bay Area even if they can afford it, and certainly not everyone is an Ed Sheeran fan.

Propositions

If we accept the axioms to be true, we can deduce further statements from them that logically follow.

Prop. 1: Inequality seems inevitable

If we accept people being different (Ax. 3), and we respect their differences in preferences in the society, they’ll end up doing different things, leading to unequal outcomes.

On the other hand, if we force people into the same things, some people will like it more than others and derive more enjoyment out of it, in my opinion, that also makes them unequal.

Prop. 2: Generalization seems inevitable

Given that people are different (Ax. 3) and resources limited (Ax. 2), it seems impossible to have an entirely personalized societal system, where we decide every matter based entirely on individual circumstances, i.e. the “the law shouldn’t apply to me, because I’m unique” argument.

For example, it’s difficult to imagine everyone getting a personalized road test for their driver’s license, a personalized dose threshold for whether they’re driving under influence, and a personalized speed limit.

It’s not even clear where to draw the line on the personalization spectrum.

Car insurance companies already take into account factors such as the driver’s age, marriage status, years of driving experience when calculating the premium. But one could always argue that they’re better than their peers. Should they consider even more factors? But that’s still making a decision about an individual based on a generalized behavior of a group, albeit a smaller one. Should they conduct an in-depth interview for every person asking for a quote? How about a dynamic premium pricing on a per trip basis? How far should we go?

Prop. 3: Winners/losers seem inevitable

Given the limited resources (Ax. 2), even taking into account people’s preferences (Ax. 3), there will always be competition for the best resources (by some common standard). And with that, there will always be winners and losers.

The best schools, universities, companies, and other social groups will have more people who want to join than they have capacity for. As a result, decisions will have to be made about who’s in and who’s not, and they will have to involve some level of generalization (Prop. 2) when matching the applicants with their selection criteria.

The people who lose out on these opportunities will naturally feel like they were unfairly treated, given the relative subjective nature of fairness (Ax. 1).

So what?

If we accept these axioms and follow them to their logical conclusions, the situation seems rather hopeless. Allegations of unfairly distributed opportunities for scarce resources doesn’t seem it’ll go away, and the Harvard/UNC case seems just like any other example of this nature.

So what’s the big deal?

It seems to me that the significance of this case comes mostly from the complex history of racial relations in the United States, which made the conversation more political than rational, and extremely emotionally charged. As a result, both sides are accusing the other of immorality while, in my opinion, it comes down to different definitions of fairness.

For African Americans, with the multitude of historical discriminations against them in the U.S., including slavery, Jim Crow laws, and more, giving them more of an opportunity for higher education seems a good thing, both for themselves and the racial integration and diversity of the institutions.

For Asian Americans, carrying the historical baggage of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the Japanese American internment camps during WW2, among others, having also worked hard to be a qualified applicant of higher education, only to have their application denied because there are simply too many of them also doesn’t seem quite right.

In isolation, both arguments seem plausible, but unfortunately there are more qualified applicants than there is capacity, so some of them have to be turned away (Prop. 3).

In my opinion, to say people who may have benefited from affirmative action deserve their places simply because “they belonged”, as Michelle Obama’s statement does, seems disingenuous, because they may have displaced others who also belonged. On the other hand, to insist the selection process to be strictly “color blind” also seems inconsiderate of the social-economically disadvantaged groups who have had much less to start with in the first place.

Moving forward

I offer no solutions here, as I believe the problem of perceived inequality and unfairness are philosophically inevitable.

What I do hope to see though, is a public conversation with less emotionally charged accusations and more constructive ideations towards a more generally acceptable societal system.

After all, no African American alive today was born a slave, and no Chinese American alive today was a direct victim of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

We’ve got to move past history to build a better future.

Credit: Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire | interactioninstitute.org, madewithangus.com